We are living in a tense political climate both locally and nationally where lawmakers seem out of sync with the needs and desires of everyday people. When local tax cuts are proposed in the midst of one of the most unstable national climates, also proposing tax cuts, it begs the question: where do our leaders think the money to fund essentials like healthcare, education and recreation will come from?

We are living in a tense political climate both locally and nationally where lawmakers seem out of sync with the needs and desires of everyday people. When local tax cuts are proposed in the midst of one of the most unstable national climates, also proposing tax cuts, it begs the question: where do our leaders think the money to fund essentials like healthcare, education and recreation will come from?

For parents born in the 1970s and beyond, it might be difficult to conceptualize a United States of America before the passage of land mark Federal laws impacting welfare, healthcare, education and the environment on the local level. Yet, in this era of increased jeopardy to continued support of such programs., parents, particularly parents with vulnerable children with replica Breitling watches disabilities must arm ourselves with factual political history of the many laws that protect our families. And such a critical process is most effective when taking into consideration that disabilities rights do not exist in a vacuum and are rather interrelated with other critical laws impacting overlapping marginalized groups that are also organized and advocating for funding and social change.

In the now classic article by Patricia McGilll Smith, former Executive Director of the National Parent Network on Disabilities, entitled “You are Not Alone: For Parents When They Learn That Their Child Has A Disability,” she states:

…When parents learn about any difficulty or problem in their child’s development, this information comes as a tremendous blow. The day that my child was diagnosed as having a disability, I was devastated — and so confused that I recall little else about those first days other than heartbreak. Another parent described this event as a ‘black sack’ being pulled down over her head, blocking her ability to hear, see and think in normal ways. Another parent described the trauma as ‘having a knife stuck’ in her heart. Perhaps these descriptions seem a bit dramatic, yet it has been my experience that they may not sufficiently describe the many emotions that flood parents’ minds and hearts when they receive any bad news about their child” – You Are Not Alone

While Smith frames isolation in  terms of emotions, this feeling translates politically with every new phase parents reach to access new services in the home, school and community once the reality of having children with disabilities has set in. It is important to note that isolation is essential to oppression. This is achieved by limiting the Breitling replica watches scope of understanding a problem. Not unique to isolation, once a person or a group of people adopt their aloneness, or isolation, as part of how they understand a problem and what they do about this problem, it is much easier to dismantle or manipulate this narrow interest group. In Paulo Freire’s book The Pedagogy of the Oppressed, he brilliantly articulates the strategy of divide and rule as a fundamental dimension of the theory of oppression. Freire states,

terms of emotions, this feeling translates politically with every new phase parents reach to access new services in the home, school and community once the reality of having children with disabilities has set in. It is important to note that isolation is essential to oppression. This is achieved by limiting the Breitling replica watches scope of understanding a problem. Not unique to isolation, once a person or a group of people adopt their aloneness, or isolation, as part of how they understand a problem and what they do about this problem, it is much easier to dismantle or manipulate this narrow interest group. In Paulo Freire’s book The Pedagogy of the Oppressed, he brilliantly articulates the strategy of divide and rule as a fundamental dimension of the theory of oppression. Freire states,

“As the oppressor minority subordinates and dominates the majority, it must divide it and keep it divided in order to remain in power. The minority cannot permit itself the luxury of tolerating the unification of the people, which would undoubtedly signify a serious threat to their own hegemony. Accordingly, the oppressors halt by any method (including violence) any action which in even incipient fashion could awaken the oppressed to the need for unity…It is in the interest of the oppressor to weaken the oppressed still further, to isolate them, to create and deepen rights among them…” – Pedagogy of the Oppressed

The study entitled “Work-Family Fit: Voices of Parents of Children with Emotional and Behavioral Disorders,” finds that one in four US households with children will have one or more children with disabilities, ranging from mild to severe, manifesting as physical, mental, or both. There are several factors informing a parent’s response to learning a child has a disability – many include socioeconomic considerations.

Beyond initial emotional response to prognosis, the reality of living with children with disabilities can be a complex arrangement of overlapping and intersecting social identities that inform the quality of life one is able to provide their child. For example, wealthy families experience raising a child Fake watches UK with a disability differently than a family in poverty. At the same time, sacrifices made in consideration in caring for a child with a disability can be informed by other factors gender, race and even immigration status. For example, mothers (more likely than fathers) frequently reduce their work hours or quit work altogether to care for their children with disabilities regardless of if they are married or single. Yet at the same time, the study entitled “Work Choices of Mothers in Families with Children with Disabilities,” found that single mothers with young children with disabilities have been found to be 17% less likely to work full-time compared to a single mother whose child does not have a disability.

Also, while there is much room for study on immigrant families with children with disabilities in the US, there is a recently defended Master’s thesis in Interdisciplinary Studies from the University of Iowa by Rochelle Renee Honey-Arcement entitled, “Immigrant parents of children with disabilities and their perceptions of their access to services and the quality of services received” (Spring 2016). In this thesis Honey-Arcement recommends the need for disabilities advocates to learn about the impact that cultural differences in values and communication, along with racism and language barriers have on accessing services. And as such, recommends a need to devise ways to get this information disseminated beyond such linguistic barriers.

The famous 1966 study by James S. Coleman entitled, “Equality of Educational Opportunity,” concluded that of all contributing factors to academic success for children, family educational and/or economic background is a bigger factor than school resources or other more popular ideas around improving student performance including: school expenditure levels, class size, and teacher quality. Coleman’s 700+ page report was released about year after then-President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, which dedicated federal funds to disadvantaged students through the Title 1 program currently under jeopardy in funding in the proposed Fiscal Year 2018 Federal Budget by the Secretary of Education Betsy Devos.

In light of the assault on public education via the current Department of Education. This, along with the economic stress of raising a child with a disability in an unstable marketplace where concepts like Universal Basic Income, as recently spoken about by Mark Zuckerburg, do not yet have community buy-in that leads to tangible local and federal policies governing such income protection practices, it is uncertain how families will be able to cope under the current political climate.

While, typically used to describe the current politics in Europe, austerity measures are a continuous and common threat in the United States and explains the ideology of many of our law makers on both sides of the isle and across various levels of government. In a recent book entitled The Violence of Austerity (2017), edited and translated by Vickie Cooper and David Whyte, explains the impact of these policies in the United Kingdom as followed:

“Austerity, a response to the aftermath of the financial crisis, continues to devastate contemporary Britain. In The Violence of Austerity, Vickie Cooper and David Whyte bring together the voices of campaigners and academics including Danny Dorling, Mary O’Hara and Rizwaan Sabir to show that rather than stimulating economic growth, austerity policies have led to a dismantling of the social systems that operated as a buffer against economic hardship, exposing austerity to be a form of systematic violence. Covering a range of famous cases of institutional violence in Britain, the book argues that police attacks on the homeless, violent evictions in the rented sector, the risks faced by people on workfare schemes, community violence in Northern Ireland and cuts to the regulation of social protection, are all being driven by reductions in public sector funding. The result is a shocking expose of the myriad ways in which austerity policies harm people in Britain.” – The Violence of Austerity‘

Put to a local framework, the DC Fiscal Policy Institute offers insight in a recent position paper by Peter Tuhtsthat entitled, “A City Breaking Apart: The Incomes of DC’s Poorest Residents Are Falling, While Economic Growth is Benefiting Better-Off Residents” states:

“The income of the poorest DC households is now lower than in most major cities, and far lower than in the DC suburbs, an especially serious problem in a region where the cost of living is among the nation’s highest. DC’s persistent income inequality is also wider than in almost any other U.S. city.” – A City Breaking Apart

With these considerations, one may ask, what does this have to do with advocating for the educational rights of children with disabilities?

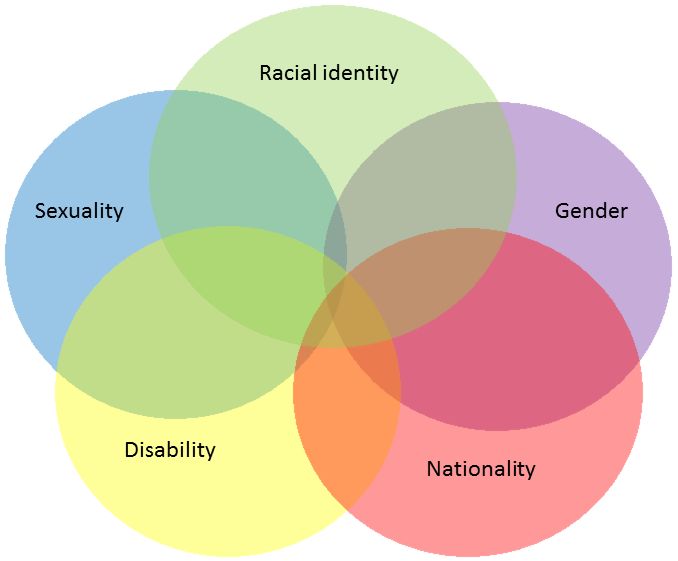

The answer is: intersectitonality. A theoretical concept coined by lawyer and scholar Kimberle Creshaw, intersectionality is a framework that describes how overlapping forms of discrimination and how structures make certain co-occuring identities (ex. single mothers, African American, LGBTQ, immigrant or homeless families raising children with disabilities) are vulnerable to exclusion and other forms of oppression. Intersectionality offers intellectual space to interrogate how certain privileges impact social outcomes and the role of institutional decision-making practices in policies and laws in protecting or exposing overlapping vulnerable groups. Crenshaw develops this concept primarily to explain the connections between gender and race; as both are impacted by patriarchal and racist systemic arrangements yet impacts other identifies such as sexuality, ability and socio-economic class status, to name a few. She argues that in the absence of an intersectionality analysis, proper understanding of social issues are undermined by our inability to develop inclusive coalitions to impact change that is beyond a singular identity.

The answer is: intersectitonality. A theoretical concept coined by lawyer and scholar Kimberle Creshaw, intersectionality is a framework that describes how overlapping forms of discrimination and how structures make certain co-occuring identities (ex. single mothers, African American, LGBTQ, immigrant or homeless families raising children with disabilities) are vulnerable to exclusion and other forms of oppression. Intersectionality offers intellectual space to interrogate how certain privileges impact social outcomes and the role of institutional decision-making practices in policies and laws in protecting or exposing overlapping vulnerable groups. Crenshaw develops this concept primarily to explain the connections between gender and race; as both are impacted by patriarchal and racist systemic arrangements yet impacts other identifies such as sexuality, ability and socio-economic class status, to name a few. She argues that in the absence of an intersectionality analysis, proper understanding of social issues are undermined by our inability to develop inclusive coalitions to impact change that is beyond a singular identity.

Specific to drawing intersections impacting children with disabilities, there are many lines that bring together a variety of oppressed categories. There are many intersectional forms of oppression when considering the challenges facing families raising children with disabilities. Beyond the classic sociological trinity of race, class and gender, there are sub-categories within this tripod that create nuances within the spectrum of geopolitical and socioeconomic challenges facing families raising children with disabilities.

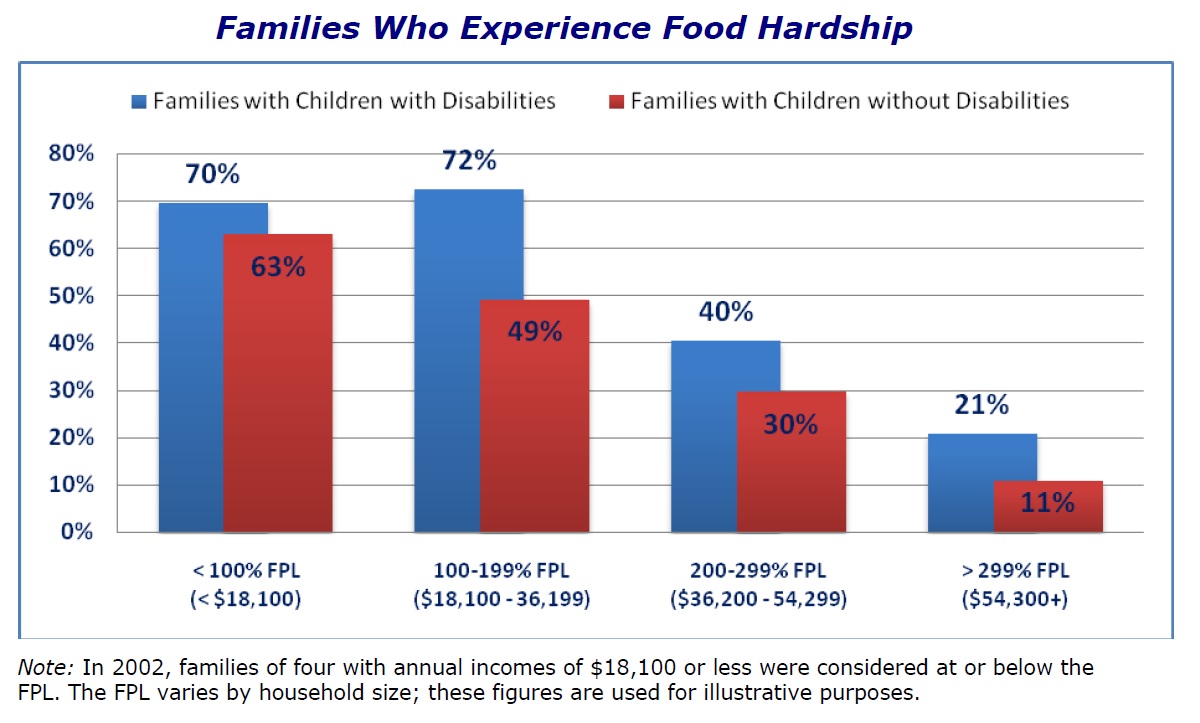

In a study entitled the “Material Hardship in US Families Raising Children with Disabilities,” highlights that compared with 16% of children without disabilities, 28% of US children with disabilities live below the federal poverty threshold due to the additional financial expenses related to the child’s disabilities including therapy costs, specialized day care, and adaptations and modifications, etc. Through analyzing the material hardship of 42,000 US households with and without children with disabilities across four (4) domains:

- Food insecurity

- Housing stability

- Telephone disconnection

- Health care access

In review of these poverty indicators, the study found that across income levels, children with disabilities and their families experienced significantly more economic constraints that families whose children don’t have a disability. A major poverty indicator is the ability to pay rent and/or other housing related utilities. The study finds that families with children with disabilities are 72% more likely than other families to have been unable to pay rent in the previous the previous year; and these families were 81% more likely to have had phone service disconnected for more than a day during the prior year because of nonpayment.

Additionally, there are significant barriers when it comes to access to health care for families with dependent children with disabilities. These children are more likely to have access to some form of health insurance coverage, such families had to delay necessary medical and dental care more often than other families.

There are many proposed solutions to this phenomenon of poverty making due to raising a child with a disability, some of which include making adjustment to Social Security Insurance and Medicaid – access to both are under jeopardy in the proposed bill in the Congress. Additionally, with a proposed $9 billion cuts to public education as proposed by Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, there is uncertainty surrounding the impact of promoting school choice in the largely deregulated charter schools and the protection of the educational rights of children with disabilities. The impact of such policies is already locally felt in Washington, DC, with 66 LEAs (as in DCPS and 65 public charter schools) , there is chaos at the base when it comes to creating policies that actually protect families with children with disabilities regardless of their school choice.

In conclusion, Martin Luther King, Jr is quoted for saying, “Power without love is reckless and abusive, and love without power is sentimental and anemic.” The framework of intersectionality offers powerful insight that must be guided by a love for humanity, in the spectrum of abilities that make up the human experience. It is an expression of love to see beyond ones own privilege. And the Inclusive Prosperity Coalition looks forward to a fruitful Summer 2017 our partnership with Georgetown University Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities, the Deputy Mayor for Education, the Deputy Mayor’s Office of Public Safety and Justice, our various City Councilmembers and many other community partners, working hand in hand to ensure that our intersections lead to solutions for protection of children and youth with disabilities in this great city.